The Demonization of Pan

The Great God Pan by Canadian-born illustrator Norman Price (1877–1951)

To the Greeks, Pan was a shepherd: he was half goat and half man, a thing of nature, certainly not the Antichrist or a being who was out to corrupt and steal men’s souls. By approximately 300 C.E., the demonization of Pan had begun, and it continued until the western world largely associated images of Pan with the devil.

“Midas, no longer lured by dreams of riches,

Took to the woods, became a nature-lover;

He worshipped Pan…”

(Ovid 303)

Such a mention of the ancient Greek god, Pan, hardly seems threatening. It certainly does not suggest that Pan was evil incarnate, yet by approximately 300 C.E., the demonization of Pan had begun, and it continued until the western world largely associated images of Pan with the devil. To the Greeks, Pan was a shepherd: he was half goat and half man, a thing of nature, certainly not the Antichrist or a being who was out to corrupt and steal men’s souls. He was lusty; he played pipes and was therefore musical; and he was a god of nature.

And though much is made in schools and textbooks of the major Olympian gods, Zeus and the gang, it is clear from archaeological evidence that Pan was the favorite god of the Greek people. “It’s a fact that there are more dedications to him than to any other…” (Pitt-Kethley xi). Perhaps this is what led Christian theologians to demonize Pan; they sensed a powerful competitor for the hearts of the people. This demonization was no accident, but rather a deliberate twisting of pagan ideals as Christianity spread its influence throughout Europe. After the Council of Nicea issued the Nicene Creed and the Roman Catholic Church was established in 325 C.E., Christian theologians (beginning with Eusebius) transformed Pan from a benign nature god to Satan, the great Adversary.

Jesus Christ and sexuality

There is some evidence to the contrary, that in fact, Pan went the other way, and was associated with Jesus Christ. The connection may not be apparent at first: how can a “minor” god of the sizable Greek pantheon have anything to do with the central figure of a monotheistic, eschatological religion? The mere suggestion of this would get someone burned at the stake during the Spanish Inquisition. But the similarities are there. For example, they were both shepherds, after a fashion. Also, neither of them were entirely divine: Jesus was supposed to be one hundred percent divine and one hundred percent human simultaneously, and Pan was likewise a god and “also an earthly being, by virtue of his mother Dryope, his occupation, and his association with man. This fusion of the human and divine in one creature has led many later Christian poets, most notably Milton, to describe Pan as a pagan prefiguration of Jesus Christ” (Baker 11). The crucial point here, however, is that such comparisons were made by poets, and mostly poets who lived after the Reformation, not by priests or bishops of the Church and certainly not by any of the popes.

The obvious problem with comparing Pan to Jesus, in the Church’s view, would be Pan’s incredible virility.

The obvious problem with comparing Pan to Jesus, in the Church’s view, would be Pan’s incredible virility. Jesus was never portrayed as a sexual being, and to this day people still feel traces of guilt about sex, as if it were an unholy act. Pan was unabashedly libidinous. A survey of statuary and bas-relief sculpture conducted by Fiona Pitt-Kethley left no doubt of this. In almost every instance she recorded, Pan’s manhood was fully aroused, “though never Priapically endowed” (xiii). With depictions such as these, Pan’s image was obviously as far away from that of Jesus as another deity could get. No member of the clergy would ever dare to draw comparisons between them when the contrast was so evident, so the poets were alone in raising Pan to a Christ figure.

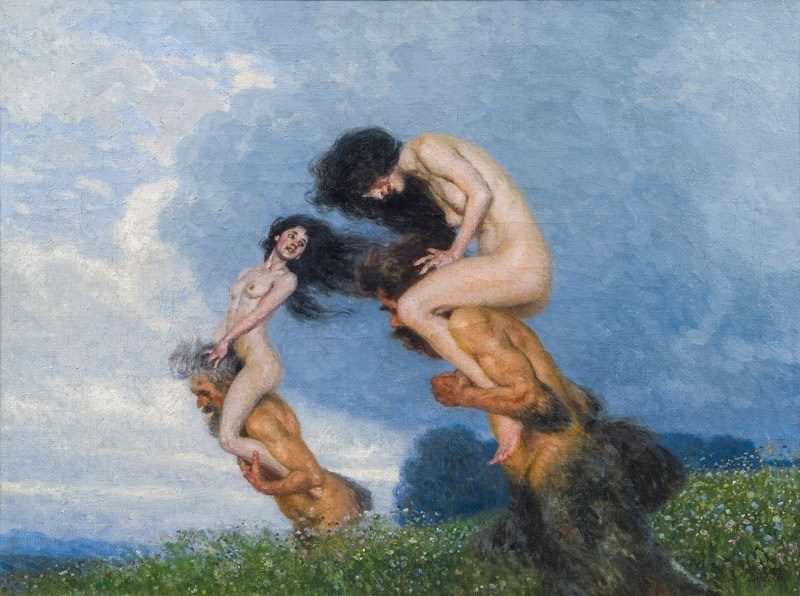

Lust by Maximillian Lenz (1860-1948)

But what is it about sexuality that makes Christianity so afraid of it, besides the fact that Jesus didn’t seem to have any? One scholar believes that since Pan was “a phallic deity like his father [Hermes], he represented sexual desire, which can be both creative and destructive” (Russell 126). The Church still preaches loudly about the destructive power of sexual immorality, and pretty much leaves the creative aspect of it for granted. Since Pan’s sexual nature was so evident, this might explain the Church’s readiness to hold up Pan as an example of profound moral turpitude. “Sexual passion, which suspends reason and easily leads to excess, was alien… to the asceticism of the Christians; a god of sexuality could easily be assimilated to the principle of evil” (Russell 126). Pan’s sexuality, when combined with his unwholesome visage, thus gave the ascetics exactly what they needed. Since he had never been attractive to begin with, and Christians were wont to associate ugliness with evil (deformations and plagues of all kinds were seen as a punishment from God for sins committed), Pan became the image of the devil. Pan’s entire physique was so gruesome to behold that the Church could almost point to Pan and say, “This is what happens to the sexually immoral.”

Christians had a tendency to equate all pagan deities with demons

Pan wasn’t the only pagan god getting his name besmirched at first. Believing in only one God and forsaking all others, Christians had a tendency to equate all pagan deities with demons. Eusebius, writing in the early fourth century, was the first to take aim specifically at Pan. In responding to Plutarch’s account of Pan’s “death” during the reign of Tiberius (who reigned during the time of Jesus’ crucifixion), Eusebius interpreted the story as evidence that God had rid humankind of its biggest demon. “As the pagan deities were demons, in the Christian view, Eusebius’, equating Pan with the daemon, seems natural and unforced” (Merivale 13). By the time of Eusebius, it might well have been natural to make such an equation; but according to A History of the Devil, such slander would have been impossible without the emergence of the Septuagint and the concept of a devil, period.

The concept of the Devil was also aided by the development of the concept of evil demons. At first, demons are morally ambivalent like the gods. Then two groups of demons are distinguished, one good and the other evil. Finally, a shift in vocabulary occurs. In the Septuagint, the good spirits are called angels and the evil spirits demons, wholly evil spiritual beings. These are now easily amalgamated with the Devil, either lending their traits to him, or being spirits subordinate to him (Russell 170).

It is not difficult to see here how Pan’s rampant sexuality, so sinful to Christians, made him an ideal candidate for demonization.

It is not difficult to see here how Pan’s rampant sexuality, so sinful to Christians, made him an ideal candidate for demonization. This defamation of a once pastoral god was part of a vast campaign of religious propaganda designed to put the fear of the devil (where the fear of God didn’t seem to work) in the people’s hearts, for Christianity had several pantheons of old gods to conquer, and a personification of evil was efficacious in helping the process along. Thanks to Christianity, Pan literally became the world’s biggest scapegoat.

The conversion of pagan Europe to Christianity took up most of the first millennium; history shows that pagan converts had problems assimilating the ideas that violence and sensual pleasure were sinful. The former is certainly obvious in the evangelical methodology of Olaf Trygvesson, king of Norway in 999 CE: “All Norway will be Christian or die” (Reston 30), he said. However, the forcible conversion of the populace was being mirrored elsewhere at the same time, and the old cycle of violence (burn, rape, and pillage one’s way to the throne) that had ruled since ancient times was curtailed enough so that civilization could begin. “The last apocalypse was a process rather than a cataclysm. It had the suddenness of forty years. Limited to Europe, its drama lay in the deliverance from terror rather than terror itself” (Renton 277).

St. Augustine was the first to demonize Pan for his sexuality

Pan of Faunus by Lovis Corinth (1858-1925)

But while Christianity might have been mildly effective in blunting Europe’s taste for violence, it is clear that it had (and still has) difficulty blunting human sexuality. With Pan and the other pagan gods, sexuality had always been something to be enjoyed, and people took great delight in imitating the gods. Trying to quell one’s desires and imitate the celibacy of Jesus was therefore a bit too much to ask, even simply confining sexuality to marriage was (and is) a problem.

No one felt this more keenly, apparently, than St. Augustine of Hippo, who rails at length in his Confessions about the perils of sexuality. He was the first to demonize Pan specifically for his sexuality (approximately 400 C.E.), going beyond the general Christian tendency to equate pagan deities with demons on general principle. “Saint Augustine, first mentioned the existence of incubi, which he thought to be forest deities; Augustine had spun both them and the succubi out of such Hellenic holdovers as Pan and his Dryads as well as other nymphs” (Massadie 275).

Augustine’s ideas were brought to America by the Puritans centuries later; they thought that the devil, horned and goat-footed, actually lived in the forest around Plymouth. Of course, the myth of his deviltry was widely spread and emphasized throughout the Middle Ages. The Church did propagate the image of Pan as the devil to give an ugly face to all of Satan’s temptations, but they were primarily concerned with snuffing out the libidinous nature of the populace, else why not choose an even uglier creature to symbolize ultimate evil? “The devil was everywhere, carved on cathedral doors and pulpit pediments, always with the same Pan-like body… an image that, in this era torn between ribaldry and Gnostic mysticism, betrayed and obvious obsession with sex” (Massadie 275).

The Church was anxious to prevent Pan from slipping back into his harmless nature

As time went on, Pan’s image as the devil continued to be reinforced – especially during the Renaissance, when ancient Greek and Roman gods regained some of their fame for awhile. The Church was anxious to prevent Pan from slipping back into his harmless nature, and so commissioned works of art appropriately: “Pan’s knobbly horns… took on a newly, diabolic meaning in Christian art… such examples are not “misinterpretations” of classical content but purposeful… Christian diabolization of pagan forms” (Camille 103).

The Christian demonization of a randy but otherwise benign nature god, seems quite clear to one living in a secular century, and it must have been irritating to those who believed in him, if they realized the purpose behind it at the time.

This Pan-like image of Satan persists in fundamental denominations today, and can be seen in comic adaptations of C.S. Lewis’ The Screwtape Letters. A horned, goat-footed devil appeared in the movie Legend, and doubtless such caricatures pop up in horror movies as well. These silly ideas about the Pan-like image of Satan are all thanks to the pioneering efforts of Eusebius and Augustine, whose ideas were perpetuated and embellished by a horde of subsequent zealous clergymen.

The Christian demonization of a randy but otherwise benign nature god, seems quite clear to one living in a secular century, and it must have been irritating to those who believed in him, if they realized the purpose behind it at the time. From all ancient sources and archaeological evidence, Pan was obviously a greatly revered, rather than greatly feared, being at one point. It was only the ascetic values of the Judeo-Christian tradition that doomed him to play the role of the ultimate bad guy. Indeed, “it is a strange comment on a changed morality that this god… should have been turned by the Christian theologians into a devil” (Woods 86), for he was the god of all nature, and thus behaving naturally, not as the incarnation of evil. ♦

This article by Kevin Hearne in 1998 was published in our VAMzzz Magazine in 2014. We thank Mr. Hearne for his permission to republish.

You may also like to read:

Witches ointment

Why did Witches Want to Ride their Broomsticks?

The incubus or succubus – nightmare or astral sex date?

Hecate – The Calling of the Crossroad Goddess

The Ancient Witch-Cult of The Basques

Walpurgis Night

Stefan Eggeler: Walpurgis Night witches, Kokain (Cocaine) and other illustrations

Witchcraft paintings – Dutch 17th century

Rosaleen Norton, Daughter of Pan

Mysteries of the Ancient Oaks

Black Cat Superstitions

The Mystical Mandrake

Little Secrets of the Poppy

Datura stramonium or jimson weed or zombi-cucumber

Mountain spirits

Wild Man or Woodwose

Sprite

Claude Gillot’s witches’ sabbat drawings

VAMzzz Publishing book:

The House of Souls is a collection of four masterpieces of horror and mystery, by Arthur Machen, first collectively published in 1906.

A Fragment of Life tells of a young couple, the Darnells, living in a London suburb. Machen gives an enormous amount of detail to illustrate the Darnells’ life only to convince the reader (and Mr. Darnell) that this is just a fragment of life or part of a greater, but hidden reality.

The White People was written in the late 1890s, and first published in 1904 in Horlick’s Magazine. A discussion between two men on the nature of evil, leads one of them to reveal a mysterious Green Book he possesses. It’s a young girl’s diary, in which she describes in ingenuous, evocative prose her strange impressions of the countryside in which she lives, as well as conversations with her nurse, who initiates her into a secret world of folklore and ritual magic…

The Great God Pan was widely denounced by the press, on publication in 1894, as degenerate and horrific because of its decadent style and sexual content. Today it is recognised as one of the greatest classics of horror. Machen’s story was only one of many at the time to focus on the Greek God Pan as a useful symbol for the power of nature and paganism.

The Inmost Light involves a doctor’s scientific experiments into occultism, and a vampiric force instigated by his unrelenting curiosity regarding the unseen elements. A mysterious gemstone is the vampire mediator, soaking the soul of the doctor’s wife and replacing it with something demonic. Dr. Black his own energy is then gradually sucked up by the stone too. In attempting to enter the forbidden and dark zone of the other worldly…

The House of Souls

A Fragment of Life / The White People / The Great God Pan / The Inmost Light

by Arthur Machen

English

ISBN 9789492355218

Paperback, book size 148 x 210 mm

336 pagesInterested? Preview and more on this book…